Facilities – Pipeline

The NEB released its recommendation to the Governor in Council (“GIC”) for the recommendation to approve the Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC (“Trans Mountain”) application for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project (“Project”), subject to 157 conditions.

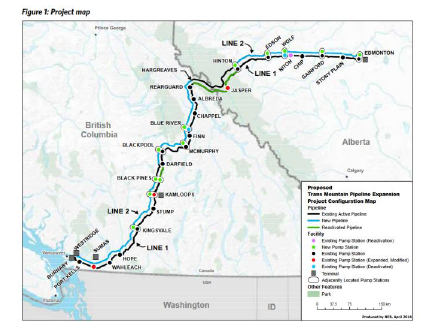

Trans Mountain applied for an expansion of its existing Trans Mountain Pipeline system from Edmonton, Alberta to Burnaby, British Columbia. Trans Mountain stated that crude oil delivered to Burnaby would be loaded onto tankers at the Westridge Marine Terminal (“WMT”) for export to areas such as Washington, California, or other markets throughout Asia. Trans Mountain proposed to twin the existing Trans Mountain Pipeline System as follows:

-

Line 1 – consisting of most of the existing pipeline segments, along with two reactivated pipeline segments; and

-

Line 2 – consisting of mostly new pipeline segments, along with two currently active pipeline segments.

Trans Mountain submitted that the Project would consist of approximately 987 kilometres of new buried pipeline. The Project would increase the capacity of the existing Trans Mountain Pipeline system from approximately 47,690 cubic metres per day (or 300,000 barrels/day) to approximately 141,500 cubic metres per day (or 890,000 barrels/day) of crude petroleum and refined products.

Trans Mountain also noted that the tanker traffic at the WMT would increase from approximately five Panamax class tankers per month (with a capacity of 75,000 metric tonnes of deadweight tonnage each) to approximately 34 Aframax class tankers per month (with a capacity of 80-120,000 metric tonnes of deadweight tonnage), depending on market demand.

The Project route was provided in a figure by the NEB in the decision, as follows:

Trans Mountain stated that it selected its preferred route using the following criteria:

-

siting the proposed corridor on, or adjacent to the existing pipeline or adjacent to easement or rights of way of other linear facilities;

-

siting the proposed corridor in a new easement selected to balance a number of engineering, construction, environmental and socio-economic factors; and

-

minimizing the length of any new easement before returning to the existing pipeline easement or other rights of way.

Trans Mountain noted that the Project would traverse a number parks and protected area in British Columbia: Finn Creek Provincial Park, North Thompson River Provincial Park Lac Du Bois Grasslands Protected Area, and Bridal Veil Falls Provincial Park. In Alberta, Trans Mountain noted that the route would traverse Jasper National Park.

Trans Mountain noted that the proposed route would primarily cross private lands (73.50 percent), and Crown lands (25.71 percent) followed by Aboriginal tracts of land (0.80 percent).

Benefits, Burdens and the NEB Recommendation

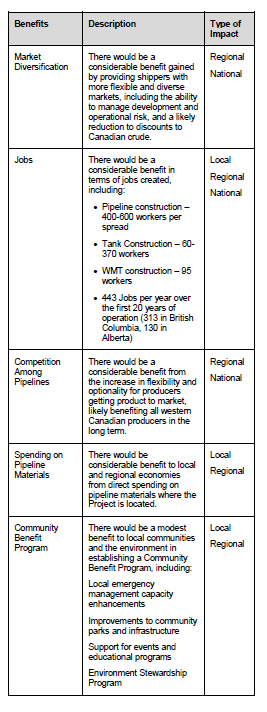

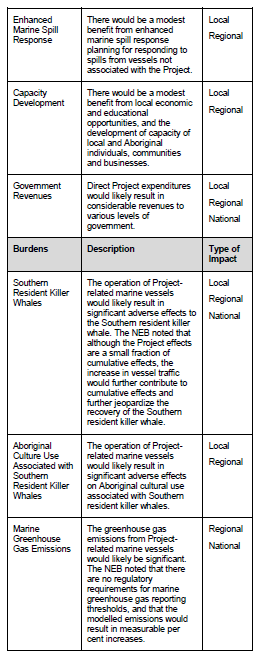

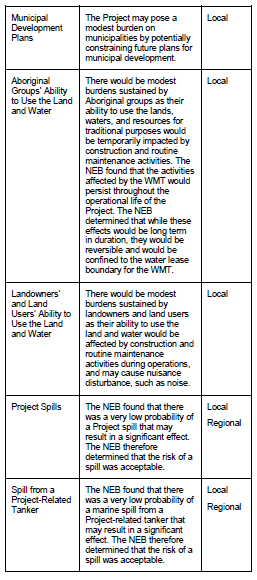

The NEB provided a summary table of benefits and burdens associated with the Project in its summary of its recommendation. The NEB noted the following:

The NEB noted that in weighing the benefits and residual burdens of the Project that it placed significant weight on the economic benefits of the Project, many of which would be realized throughout Canada. The NEB noted that such a national perspective was critical in the NEB’s finding that the Project would be in the Canadian public interest.

The NEB found that the Project was in Canada’s public interest, and recommended that the GIC approve the Project, and direct the NEB to issue the necessary certificates of public convenience and necessity (“CPCN”).

Regulating through the Project Lifecycle

The NEB noted that if the Project is approved and Trans Mountain proceeds with the Project, it would be required to comply with all conditions included in the CPCN and associated instruments.

Among the conditions imposed by the NEB, during the construction phase, Trans Mountain must have qualified inspectors on site to oversee construction, and have the NEB conduct field inspections.

Trans Mountain would also be required to apply for leave to open the Project under section 47 of the NEB Act.

The NEB also imposed conditions during the operations phase of the Project, and required Trans Mountain to restore its rights of way and temporary work areas to a condition similar to the surrounding environment, as well as monitor the rights of way for any environmental issues created from construction and operation. The NEB further imposed as a condition that it would inspect the Project post-construction to verify compliance with conditions imposed.

With respect to compliance verification and enforcement, the NEB stated that its conditions and compliance programs were designed to ensure the safe and effective environmental protection throughout the lifecycle of the Project.

The NEB explained that it applies a risk-informed approach in planning compliance and verification activities, evaluating facilities on an ongoing basis to determine the appropriate compliance verification activities.

Public Consultation

Trans Mountain submitted that its Stakeholder Engagement Program (“SEP”) was designed to foster participation from the public who have an interest in the Project. Trans Mountain submitted that it consulted with local governments and community leaders to seek input for its SEP in 2011. Trans Mountain stated that it identified a number of stakeholder groups that could be interested in the Project, including landowners, government authorities, industry and businesses, environmental non-governmental organizations, special interest groups, as well as the general public as part of its SEP. Specific to the WMT, Trans Mountain submitted that it extended its stakeholder consultation efforts to include coastal communities beyond the WMT in Burnaby, BC.

Trans Mountain submitted that its SEP was conducted beginning in 2012, and is an ongoing process, including open houses, community workshops and online discussion activities, as well as face-to-face meetings, presentations, public forums and technical meetings. Trans Mountain stated that its activities included:

-

159 open houses along the pipeline and WMT corridor;

-

1,700 meetings between Project team members and stakeholder groups;

-

550 phone inquiries, and approximately 1,500 emails,

-

Approximately 950 media inquiries and 430 media interviews.

Trans Mountain further noted that various documents were made available in multiple languages, including French, Chinese, Punjabi and Korean to ensure its communications reached as broad an audience as possible.

Trans Mountain submitted that it incorporated stakeholder feedback as part of its SEP by, for example, making the following changes to the design of the Project:

-

Exploring alternatives to avoid the use of temporary work spaces in Colony Farm Regional Park;

-

Establishing access planes, construction schedules and compensation plans to minimize impacts on the Ledgeview Golf Course;

-

Implementing horizontal directional drilling (“HDD”) entry and exit points more than 30 metres away from watercourse and riparian areas; and

-

Assigning community construction liaison roles as part of its construction team as a key point of contact for local communities.

The City of Abbotsford, Township of Langley, Fraser Valley Regional District, Fraser-Fort George Regional District & Village of Valemount (the “Municipalities”) expressed concerns regarding consultation, including a failure to communicate and incorporate feedback on important matters that would impact the Municipalities. The Municipalities also stated that Trans Mountain had not fully recorded all of the commitments made to them.

Trans Mountain replied stating that it maintained regular engagement with governmental entities, and would continue to do so to address specific municipal issues and concerns through joint technical working groups.

The NEB held that Trans Mountain developed and implemented a broadly based SEP, offering numerous opportunities for stakeholders to provide their views on the Project.

The NEB stated that it expected parties to engage by communicating their concerns to one another and to make themselves available to discuss potential solutions on an ongoing basis. The NEB noted in particular that the City of Burnaby declined a number of opportunities to meet with Trans Mountain, and held that when a municipality declines an opportunity to engage, it effectively diminishes the quality of information available both to the company proposing a facility, and the NEB itself, creating a potential for less than satisfactory solutions to stakeholder concerns.

The NEB imposed a condition on Trans Mountain to require that it establish terms of reference for its technical working groups in collaboration with affected municipal government, facility owners and operators prior to commencing construction. The NEB also imposed a condition requiring Trans Mountain to file with the NEB reports of the meetings of the technical working groups, allowing the NEB some visibility into how Trans Mountain is addressing stakeholder concerns on an ongoing basis.

The NEB further imposed a condition requiring the tracking of commitments prior to the start of construction, and to file the same with the NEB.

Taking into account the above conditions, and Trans Mountain’s commitments to stakeholders, the NEB held that Trans Mountain can effectively engage the public, landowners and other stakeholders, and address any issues raised throughout the life of the Project.

Aboriginal Matters

Trans Mountain stated it viewed working with Aboriginal communities along the Project route as part of its commitment to transparent consultation and communication, and would build lasting and mutually beneficial relationships.

Trans Mountain submitted that its Aboriginal consultation program commenced in 2012, and remains ongoing. Trans Mountain stated that it consulted with Aboriginal groups within a 10-kilometer radius around the Project area for consultation in British Columbia, and a 100-kilometer radius in Alberta (due primarily to uncertainty with the establishment of traditional territories).

Trans Mountain also extended its Aboriginal engagement program to include coastal communities beyond the pipelines terminus at the WMT, including communities on Vancouver Island and surrounding Gulf Islands along the established marine shipping corridors. Trans Mountain submitted that it engaged in consultation with 120 Aboriginal groups, two non-land based British Columbia Métis groups, and 11 Aboriginal associations, councils and tribes.

Trans Mountain stated that it focused on enhancing trusting and respectful relationships, and its consultation activities included:

-

Sharing Project information;

-

Negotiating group and community-specific protocols, capacity agreements, and mutual benefit agreements;

-

Facilitating traditional land use (“TLU”) studies and traditional marine resource use (“TMRU”) studies, as well as traditional ecological knowledge (“TEK”) studies;

-

Identifying potential impacts and addressing concerns;

-

Discussing the adequacy of planned impact mitigation; and

-

Identifying education, training, employment and procurement opportunities.

Trans Mountain estimated that it completed more than 24,000 engagement activities with Aboriginal groups. Trans Mountain noted that its engagement process varied from group to group, as some preferred open processes, whereas others preferred strictly confidential meetings.

Trans Mountain submitted that as a result of its engagement activities, it identified air and water quality, fish and fish habitat, wetlands, vegetation, wildlife and wildlife habitat and species at risk impacts that required addressing. A total of 52 Aboriginal communities participated in TLU studies, 15 Aboriginal communities participated in TMRU studies, and 57 Aboriginal communities provided TEK studies.

Trans Mountain also noted it received a total of 30 letters of support from Aboriginal groups, and executed 94 agreements including letters of understanding, with an aggregate value of $36 million.

A total of 24 Aboriginal groups filed evidence and raised concerns regarding the engagement process, Project benefits, emergency response planning, capacity funding, and Project-related effects on the assertion of Aboriginal rights and title. Many of the groups submitted that Trans Mountain did not adequately discuss mitigation measures, or failed to formalize commitments, and that Trans Mountain did not consult with them until the group itself advised Trans Mountain of its concerns.

The Government of Canada submitted that it would rely on the NEB’s review process to the extent possible to identify and consider and address any adverse impacts on potential or established Aboriginal and treaty rights resulting from the Project.

The Government of Canada outlined its approach to consultation in four phases:

-

Phase I: Initial engagement, ranging from submission of Project description to the start of the NEB review process;

-

Phase II: NEB hearings;

-

Phase III: Post-NEB hearings to a Governor in Council decision on the Project; and

-

Phase IV: Regulatory permitting, ranging from the Governor in Council decision, to the issuance of any required approvals.

The Government of Canada noted that its federal authorities would work together to ensure that the legal duty to consult Aboriginal groups is fulfilled and performed in a manner that is integrated with its other assessments and reviews for the Project.

The NEB held that while it does not owe a duty to consult itself, it recognized that the Government of Canada was relying on its processes to meet its own duties to consult, given the NEB’s robust and inclusive process, and remedial powers. The NEB determined that it was satisfied that its decisions and recommendations were consistent with section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 regarding the duty to consult with Aboriginal groups.

In assessing the interests of each group that may be impacted, the NEB looked to the measures that could be employed to mitigate each group’s concerns, and then considered all of the benefits and burdens of the Project as a whole, balancing Aboriginal concerns with other interests and concerns before determining whether the Project was in the public interest.

The NEB held that Trans Mountain met the expectations of the NEB’s filing manual, including information about the Project’s design, operations and potential environmental, social and economic effects. The NEB found that the criteria used by Trans Mountain to identify potentially affected Aboriginal groups were appropriate in considering their proximity to the proposed right of way of the Project. The NEB held that Trans Mountain provided opportunities to Aboriginal groups to raise and discuss the potential impacts of the Project with Trans Mountain. The NEB further found that Trans Mountain considered information provided by Aboriginal groups throughout consultations, and made a number of changes to the Project as a result of this information, including reconfiguring the proposed route in the Upper Fraser River, Upper North Thompson River Valley, and the Peters Indian Reserve No. 1A.

The NEB imposed conditions on Trans Mountain requiring them to file with the NEB, a plan for monitoring the implementation of training and education opportunities, and to file a local, regional and Aboriginal skills and business inventory with the NEB.

As the NEB found that the final design of the process was an iterative process, the NEB required Trans Mountain to continue to consult with potentially affected Aboriginal groups on issues such as routing, and mitigation measures.

Pipeline and Facility Integrity

Trans Mountain submitted that the construction of the Project involved the following pipe sizes and lengths:

-

Approximately 339 km of 914 mm pipeline from Edmonton to Hinton, Alberta;

-

Approximately 121 km of 1067 mm outside diameter pipeline from Hargreaves to Blue River, British Columbia;

-

Approximately 158 km of 914 mm pipeline from Blue River to Darfield, British Columbia; and

-

Approximately 368 km of 914 mm pipeline from Black Pines to the Burnaby Terminal, British Columbia.

Trans Mountain stated that its tanks at the current storage facilities on the Trans Mountain system had a combined capacity of 1,718,690 cubic meters in 57 tanks. Trans Mountain estimated an additional 20 tanks with a combined capacity of approximately 876,040 cubic meters, that would be constructed within the existing terminal property.

Trans Mountain submitted that the pipeline would all be designed, constructed, operated, maintained and abandoned in accordance with the Onshore Pipeline Regulations and with CSA Z662-15 standards. Trans Mountain also committed to complying with the requirements of various industry codes, standards, specifications, and recommended practices, and committed to implement failure prevention and spill mitigation measures in its design to achieve risk levels that are as low as reasonably practicable (“ALARP”).

Trans Mountain estimated that, based on a design flow rate of 90,370 cubic meters per day, that it would require 11 pump stations to operate the pipeline at an acceptable availability factor, assuming planned shutdowns for maintenance, and other operational flexibility parameters.

Trans Mountain proposed to install 55 check valves, 72 remote mainline block valves (71 of which would be automated) and 12 mainline block valves and 11 associated check valves located at new pump stations. Specific locations of each valve would be subject to the iterative detailed design and engineering process, in order to best protect the environment. Trans Mountain proposed to use remote mainline block valves with check valves on the downstream side of major watercourse crossings, and not automatic shut-off valves.

Trans Mountain proposed to implement watercourse crossing methods using either open-cut, trenchless or isolated methods. Trans Mountain submitted that its decision to use each method would vary depending on site-specific hazards and environmental considerations. Trans Mountain submitted that it had identified 23 major watercourse crossings as being favourable for isolated crossings using HDD.

Trans Mountain submitted that it planned to provide point-specific maximum operating pressures for the Project, which are expected to vary between 6,000 and 10,000 kPa.

Trans Mountain noted that it considered a theoretical future expansion scenario of 124,010 cubic meters per day, which would require installing new pipeline segments, and additional pumping units.

The NEB determined that the proposed design approach and standards comply with the current regulations. The NEB held that Trans Mountain followed accepted engineering practices during the conceptual and preliminary design phases. With respect to minimum wall thicknesses however, the NEB imposed a condition on Trans Mountain to undertake a risk assessment to identify the locations where heavier walled pipe was required.

While the NEB noted Trans Mountain’s commitment to ensure that risk was managed to levels that were ALARP, it found that Trans Mountain had not provided sufficient information regarding risk scores taking into account failure prevention and spill mitigation measures. Accordingly, the NEB imposed a condition on Trans Mountain requiring it to file an updated risk assessment for the Project with the NEB.

The NEB imposed a condition on Trans Mountain requiring it to reassess the feasibility of HDD crossings on major watercourses based on the outcomes of its detailed engineering and design, and file the feasibility and design reports with the NEB.

Construction and Operations

Trans Mountain submitted that it would develop a Health and Safety Management Plan (“HSMP”) during the detailed engineering and design phase to reduce risk, and protect the health and safety of workers and the public during construction. Trans Mountain submitted that it would be the prime contractor for pump stations, terminals and other facilities, however, external contractors would be brought in to:

-

Conduct risk assessments for construction of the assigned Project component;

-

Developing and implementing Project Specific Safety Plans (“PSSP”) to align with the HSMP; and

-

Submit the PSSP to Trans Mountain for approval at least 60 days prior to commencing construction.

Trans Mountain also committed to developing a Traffic and Access Control Management Plan (“TACMP”) where plans may directly affect public safety during construction. In addition, Trans Mountain committed to develop and implement blasting management plans, fire prevention and fire contingency plans, and a noise control plan.

Trans Mountain stated that controls to ensure public safety during construction would be determined through its detailed construction planning and consultation efforts with municipal authorities and stakeholders. Any additional controls would be integrated into the HSMP and PSSPs. Trans Mountain further committed to a communications program to ensure local businesses and the public were made aware of any potential construction impacts, including general safety requirements, lane restrictions, road closures and alternate access plans.

Trans Mountain noted that access for emergency services would be a critical component in its TACMPs and local traffic control plans, to ensure that emergency response providers are made aware of any potential traffic impacts or disruptions caused by the Project.

The NEB held that it would impose a condition requiring a submission of the manuals and plans proposed by Trans Mountain to the NEB in advance of construction. The NEB also determined that it would require more information following detailed design work to ensure that work conducted along the Project can be completed safely, and accordingly imposed a condition requiring the submission of, among other items, confined space entry procedures.

With respect to emergency preparedness, Trans Mountain committed to develop and implement a construction Emergency Response Plan (“ERP”) separate from Trans Mountain’s ERP for operations. Trans Mountain submitted that its construction ERP would be designed to ensure timely and appropriate emergency response in compliance with all applicable regulatory and legislative requirements, and would guide the development of site-specific ERPs. Each site-specific ERP would address injury and health incidents, environmental damage, fires, floods, earthquakes, rock slides, avalanches, sabotage, trespass and other emergency situations that could occur during construction.

The NEB held that it would impose a condition on Trans Mountain requiring the submission of its construction ERPs in advance of construction to ensure that regulatory requirements are met and that potential emergencies during construction are addressed.

Trans Mountain submitted that, if approved, the Project would be integrated with Trans Mountain’s existing programs and management systems. With respect to the safety and security management aspects of the programs, Trans Mountain submitted that it would operate the Project in accordance with its current Integrated Safety and Loss Management System (“ISLMS”). Trans Mountain submitted that the ISLMS ensured that risks to its employees, contractors, the public and the environment were minimized.

The B.C. Wildlife Federation commented that security programs and systems should extend to any parts of the Project with unburied or exposed pipe, including expansion joints or pigging stations, as these facilities may be targets for vandalism.

Some participants expressed concerns regarding a lack of trust in Trans Mountain and its affiliates’ safety record in particular. However, the NEB noted that a number of comments collected by Simon Fraser Student Society and The Graduate Student Society at Simon Fraser noted an overall opposition to the pipeline. The data provided indicated that the infrequency of serious incidents, the need for oil and the relative safety of pipeline transport compared to rail were themes that the Simon Fraser Student Society noted were supportive of the proposed Project.

Trans Mountain responded that security programs and systems would extend to all parts of the Project during construction and operations, including unburied segments.

In its findings, the NEB imposed a condition requiring Trans Mountain to confirm, prior to commencing operations, that it update its operations security management program to incorporate the Project. Due to the sensitive nature of such plans, Trans Mountain was not required to file a copy with the NEB. However, the NEB noted that the security management programs would be subject to assessment and ongoing NEB lifecycle compliance verification.

Trans Mountain submitted that it would provide a qualified and experienced team to inspect all phases of construction activities to ensure:

-

Compliance with procedures, specifications and drawings;

-

Compliance with legislative requirements, permit conditions and other undertakings; and

-

Conformance with Project health, safety, security and environmental plans and procedures.

Some commenters expressed concerns with how the NEB would enforce Project conditions, noting a general perception that conditions imposed were essentially self-reporting checklists for Trans Mountain, with little oversight from the NEB. Many commenters, in respect of the draft conditions released by the NEB, submitted that the phrase “unless the NEB otherwise directs” in many of the conditions, would give the NEB excessive power to alter conditions, or release Trans Mountain from compliance altogether.

The NEB, in providing its findings, imposed five overarching conditions, the effect of which, the NEB held would make all commitments, plans and programs referenced or agreed to on the record of the proceeding, regulatory requirements of the NEB. The NEB further directed Trans Mountain to file commitments tracking tables, phased filing information, a list of temporary infrastructure sites, construction schedules, construction progress reports, and a signed confirmation of Project completion and compliance. The NEB also explained that the phrase “unless the NEB otherwise directs” is to provide the NEB with flexibility to vary conditions in a timely manner, without requiring Governor in Council approval for minor items. However, the NEB stated that for larger amendments or changes to the Project, Trans Mountain would be required to submit an application to the NEB pursuant to section 21 of the NEB Act.

Environmental Behaviour of Spilled Oil

Trans Mountain submitted that oil spills on land tend to move downslope, sink downward under gravity, and spread horizontally and in the subsurface. Trans Mountain noted that oil continues to lose mass once spilled, either through dissolution, evaporation or biodegradation. Trans Mountain submitted that the process of depletion slows over time, as remaining complex hydrocarbons are more prone to resist weathering and depletion.

Trans Mountain submitted that the weathering process in an aquatic environment was substantially the same in freshwater and marine environments. Spills can generally be expected to initially float on the surface, except where the water is turbulent enough to entrain the spilled oil, or create an emulsion.

Trans Mountain submitted that during the weathering process, spilled oils may sink after lighter hydrocarbons evaporate or dissolve, and the remaining oil mixture is denser than water. However, Trans Mountain explained that different factors can affect the speed of such changes, including temperature, wind speeds, wave heights, salinity, sedimentary concentrations, and oil composition.

Trans Mountain stated that its tariff on the Project would limit the maximum density of oil at 940 kilograms per cubic meter and a maximum viscosity of 350 centistokes. Trans Mountain expected that, in the event of a spill, the diluted bitumen transported on the Project would likely behave in a manner similar to Bunker C fuel oil, which typically floats on the water with a slightly lower density than water, and may form viscous emulsions within 24 hours of a spill.

Trans Mountain modelled a worst case spill volume of approximately 1,250 to 2,700 cubic meters at several locations on the Project. Trans Mountain submitted that its model indicated that the majority of the oil spilled was expected to strand along the shorelines, as the suspended sediment concentrations (in the Fraser River) were seen as much lower, and therefore not as prone to sinking as other waterways. Trans Mountain stated that the expected length of affected shoreline ranged from 25 kilometers in summer, to up to 36 kilometers in winter, with approximately 74 percent being trapped on shore.

Several Aboriginal groups, the City of Vancouver and the City of Burnaby took issue with Trans Mountain’s modelling results, submitting that the oil’s physical and chemical properties were not assessed, and weathering was not taken into account in the modelling assumptions. Each also took issue with the modelled spill sizes, submitting that spill volumes ranging from 8,000 to 16,000 cubic meters in the Burrard Inlet was much more realistic for a spill near the WMT.

The NEB held that the literature was clear that although oil could typically submerge, it would not typically sink in large quantities nor float as a cohesive mat. However, the NEB determined that sinking of spilled oil would likely be limited in quantity, and only after significant weathering had occurred. The NEB noted that the potential for oil submergence would need to be considered by Trans Mountain in its emergency response planning.

The NEB also accepted that a majority of oil spilled on waterways would likely strand on the shorelines, which would necessitate challenging clean-up activities, due to the viscous and persistent nature of weather-diluted bitumen.

Emergency Prevention

Trans Mountain submitted that its primary goal was the prevention of spill, and it would employ management system and resources to ensure that this goal is achieved by the Project.

Trans Mountain noted that spill prevention and mitigation was embedded throughout the full Project lifecycle, and started with the risk assessment and engineering designs. Trans Mountain stated that its pipeline integrity management program would help ensure long-term spill prevention, and that its 60 year operating history demonstrates the low probability of a large pipeline spill. Notably, Trans Mountain proposed to integrate the Project into its existing emergency response and prevention strategies and plans, which would be enhanced further during detailed design and engineering.

Trans Mountain noted that from 1961 to 2013, it had reported 81 spills to the NEB, including a number that were under the reportable limits and did not cause any environmental damage. Trans Mountain also noted that no reportable spill events have occurred on its Anchor Loop facilities that go through Jasper National Park and Mount Robson Provincial Park.

Trans Mountain noted that after third party damage to its pipeline occurred due to a contractor for the City of Burnaby, it implemented a Pipeline Protection Department. Pipelines are protected through markings, issuance of safe work permits and responses to British Columbia and Alberta One Call requests.

A number of interveners requested further clarification on how human error would factor into Trans Mountain’s spill response times in Trans Mountain’s modelled scenarios. Trans Mountain noted that human error is a key consideration in the development of procedures that must be followed at its control centre, and such considerations are built into its training programs. Trans Mountain also noted that human error can be mitigated through enhanced communication built into control centre procedures.

At the WMT, Trans Mountain submitted that it would deploy at all times a containment boom around any ships at the WMT, so that in a worst case scenario, only 20 percent of oil would escape (or approximately 32 cubic metres according to Trans Mountain’s modelling). Trans Mountain also submitted that it will enact wind speed limits for safe loading of tankers at the WMT in the detailed design phase.

Trans Mountain submitted that it would use inert gas on its crude oil tankers to virtually eliminate the risk of cargo-related fire and explosions.

As part of its Emergency Management Plan (“EMP”), Trans Mountain would produce the following plans and supporting documents for the pipelines, terminals and tank farms:

-

the Incident Command System (ICS) Guide;

-

Emergency Response Plans (ERPs): Westridge Marine Terminal ERP, Trans Mountain Pipeline ERP, Terminal and Tank Farms ERP;

-

Control Point Manual;

-

Tactical Response Plans (e.g., submerged and sunken oil);

-

Geographic Response Plans;

-

Trans Mountain Field Guide;

-

Fire Safety Plans; and

-

Fire Pre-Plans.

Trans Mountain noted that in the event of a spill, it would take the following immediate steps in response:

-

Immediate shutdown of pipeline or other source of release and allow pressure to dissipate to prevent additional release of hydrocarbon and isolate the source of the spill from the rest of the system;

-

Immediately contact local emergency services and trained Trans Mountain technicians for dispatch to the location, to help secure the area and commence air monitoring to ensure air quality for those in the immediate vicinity;

-

Control centre issues an Emergency Response Line (ERL) notification to the Incident Management Team (IMT). Upon notification the IMT calls the conferencing line to get information about the incident and begin pre-assigned response duties;

-

Immediately following the ERL conference call, Trans Mountain notifies the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) and NEB;

-

Liaison Officer begins notifications to other groups not included in the above notifications;

-

Logistics Section Chief begins identification of resources required for the response and ordering supplies and equipment; and

-

Planning Section Chief begins planning recovery operations and contacting team members required including the Environmental Unit Leader.

With respect to specific spill response techniques, Trans Mountain submitted that it would respond to the unique requirements of any spill at its facilities, and provided the following examples of response strategies:

-

capturing the oil where currents and hydrographic conditions are amenable to the deployment of oleophilic material to trap the oil;

-

remobilization, containment, and removal of the oil through agitation of sediments (raking, dragging, pneumatic agitation);

-

bulk removal of the oil through pumping and/or dredging; or

-

long-term monitoring and natural attenuation in areas where remedial actions pose more harm than benefit.

Trans Mountain stated that mobilization of crews for emergency response would begin immediately, and has pre-designated incident command posts and staging areas at locations along the current pipeline corridor and in communities where its facilities are located. Trans Mountain also noted that for preparation, it would work with external emergency response service, such as through annual training with external agencies.

Trans Mountain committed to enhance its year-round emergency response capacity by developing geographic response plans (“GRP”) to account for the varying terrain across the pipeline corridor. Trans Mountain submitted that its GRP would include:

-

A review of both Lines 1 and 2 with production of a response capability analysis, which will serve as a key foundational element for the new GRPs that would be developed;

-

Development of a complete set of GRPs covering both Lines 1 and 2. These GRPs will provide responders with guidance and detailed information on access, deployment and product ;

-

Recovery as well as strategies and tactics relevant to environmental conditions throughout the year;

-

Guidance for KMC responders for other environmental factors such as full or partial ice cover of rivers, streams and lakes, forest fire and smoke, avalanche and flooding conditions;

-

A full review of control points including spacing, access suitability under various environmental conditions and others;

-

Consultation with First Nations, local and regional governments, as well as Trans Mountain’s existing mutual aid partners; and

-

Shoreline Cleanup and Assessment Technique (SCAT) guidance.

Many municipalities expressed concern over the ability of their own first responders, such as the RCMP, to mitigate a major fire event, such as a tank fire, storage tank boil over, or release of toxic gases. The City of Port Moody and the City of Kamloops stated that Trans Mountain provided scant information regarding the resources that would be directed to their municipalities in the event of a spill or accident, and felt ill equipped about how to respond to a spill or accident. Each of the municipalities and the Province of British Columbia requested a full disclosure of Trans Mountain’s EMP to afford them an opportunity to evaluate its adequacy.

Trans Mountain replied by committing to enhancing its fire detection, mitigation and prevention measures at its Burnaby Terminal. Trans Mountain will include industry leading fire protection equipment, and full-surface fire-fighting foam suppressions systems. Trans Mountain estimated that industrial firefighting contractors would be capable of responding to an incident within 6 to 12 hours.

Trans Mountain also noted that, when working with municipalities after an incident, it prefers to enter into a unified command with municipal, provincial and federal authorities to ensure a thorough response to the incident, and prioritize objectives without redundancy.

The NEB held that while all possible environmental conditions cannot be known or replicated, it nonetheless expects companies to be prepared for spills of all sizes and in all conditions.

The NEB held that it was satisfied with Trans Mountain’s commitment to review and revise its EMP to address the needs of expanding its system due to the Project. The NEB was satisfied with Trans Mountain’s commitment to consult with first responders and communities with respect to changes to the EMP. The NEB also imposed conditions reflecting its findings on Trans Mountain’s EMP.

The NEB found that the broad range of spill prevention and mitigation measures committed to by Trans Mountain, including deploying booms around tankers, were comprehensive and appropriate. However, the NEB determined that the 6 to 12 hour response time for firefighting crews was inadequate. The NEB therefore imposed a condition requiring Trans Mountain to complete a needs assessment to develop appropriate firefighting capacity in response to a fire at the WMT and at the Edmonton, Sumas and Burnaby Terminals on the Trans Mountain pipeline system.

The NEB reiterated that no spill is acceptable at any NEB regulated facilities. In the event of a spill, the NEB determined that incorporating the project into Trans Mountain’s existing emergency management programs at its existing facilities would help Trans Mountain respond to and manage an incident on the Project more effectively.

Environmental Assessment

The NEB noted that the Project met the requirements of the Regulations Designating Physical Activities under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (“CEAA 2012”), and as a result, the NEB was required to conduct an environmental assessment (“EA”) for the Project.

The NEB summarized the scope of the EA as comprised of the following three elements:

-

The physical works and activities making up the Project (as described by Trans Mountain in its application and subsequent filings).

-

The biophysical and socio-economic elements that are likely to be affected by the Project.

-

The factors that must be taken into account in conducting an environmental assessment (described in section 19 of the CEAA 2012).

The NEB also determined that upstream and downstream activities (with the exception of Project-related shipping activities) would not form part of the EA, given that the Project did not include any upstream or downstream developments, nor did it depend on any particular project for a feedstock, and was therefore not necessarily incidental to Project approval.

The NEB noted that it examined the potential environmental impacts of the Project on marine fish, fish habitat, species listed under the Species At Risk Act and their respective habitat, plant life, the mitigation measures proposed by Trans Mountain, as well as the possibility of accidents and malfunctions.

The NEB noted that it used a spatial and temporal boundary for each valued component in the Project area. Where it found any effects that were predicted to remain after mitigation measures proposed by Trans Mountain, the NEB assessed the cumulative effects of all physical activities and facilities in the area, in addition to the Project itself.

Trans Mountain submitted that the NEB should examine the Project’s contribution to cumulative effects, rather than the total cumulative effects for the purposes of the EA.

The NEB rejected Trans Mountain’s position, holding that the CEAA 2012 requires examining the cumulative environmental effects that are likely to result from the Project, in combination with other physical activities that have been or will be carried out.

With respect to air quality and emissions, Trans Mountain submitted that overall air quality was very good with few exceedances of the relevant ambient air quality objectives, and that all predicted project related concentrations of emissions and particles would meet existing guidelines, except where existing exceedances are already occurring, such as at the Edmonton Terminal and WMT.

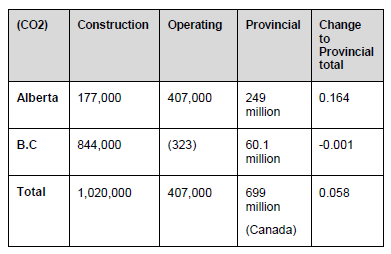

Trans Mountain also provided a summary of anticipated Project related emissions in the following table:

Many interveners took issue with Trans Mountain’s air assessment modelling, submitting that Trans Mountain excluded relevant processes, or assumed near perfect operation of equipment, such as volatile organic compound collection equipment.

In noting the potential difficulties in verifying and validating air quality modelling, the NEB directed Trans Mountain to develop and implement air emissions management plans to protect the environment and human health, and to consult with stakeholders in developing the same. The NEB also required Trans Mountain to develop baseline data for emissions monitoring at the Edmonton, Sumas, WMT and Burnaby terminals.

The NEB determined that the air emissions from construction activities were likely to be intermittent, localized, reversible and of limited duration, and was therefore not likely to cause significant adverse effects. However, the NEB still imposed a condition requiring Trans Mountain to develop an offset plan for the Project’s entire direct construction-related greenhouse gas emissions that are determined post-construction, to ensure no net emissions from construction. The NEB determined that the emissions anticipated during operations would be below national reporting thresholds, and accordingly were not considered significant.

With respect to watercourse impacts and crossing methods, Trans Mountain proposed to implement a number of mitigation measures to address potential impacts, including:

-

hydraulic isolation will be implemented for any small to medium sized streams that are hydraulically connected to fish habitat;

-

fish salvages at each isolated trenched crossing and at all fish-bearing crossings;

-

water quality monitoring for suspended sediment during trenchless and isolated trenched;

-

crossings of watercourses with high sensitivity fish habitat;

-

working within the least-risk biological windows; and

-

completing spawning surveys before and during construction.

The NEB held that finalized, site-specific information was needed to make an accurate serious harm determination, despite the mitigation measures proposed. Accordingly, the NEB directed Trans Mountain to file site-specific information for each proposed crossing as well as impacts on fish and fish habitat, prior to construction. The NEB also directed Trans Mountain to file any authorizations obtained from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans with the NEB prior to construction.

The NEB also imposed general conditions on crossing methods for watercourses, directing Trans Mountain to employ trenchless water crossing methods (such as HDD) if working in the critical habitat of Nooksack dace and Salish sucker fish.

With respect to impacts on plants and vegetation, Trans Mountain noted that long term loss of native vegetation would occur in the long term on its facilities, comprising approximately 2,231 hectares of native vegetation. Trans Mountain noted that disturbed areas would revegetate after construction, albeit in an altered state due to right of way maintenance obligations. Trans Mountain proposed the following mitigation measures for rare plants and lichens:

-

complete avoidance would be adopted for rare plants, lichens, and communities ranked imperiled or critically imperiled, and for species or critical habitat that are protected under provincial or federal legislation, subject to factors such as construction and workers’ safety;

-

disturbance reduction could include measures such as placement of protective structures over plants of concern, and restricting use of herbicide near vegetation communities or sub-populations; and

-

where avoidance and disturbance reduction are not feasible, alternative reclamation techniques would be used, such as propagating and transplanting to suitable receiving sites, and stripping the upper 15 cm of topsoil separately where feasible to make use of the existing seed bank.

Trans Mountain also proposed to establish baseline data for rare plants, and monitor data on and off the right of way.

The NEB held that Trans Mountain must file environmental protection plans, reclamation management plans, access management plans, and rare plant species discovery contingency plans prior to construction.

The NEB determined that offsets for rare plant impacts are not always successful, and stressed the importance of avoidance and mitigation to reduce any adverse effects. In making this finding, the NEB held that Trans Mountain’s proposed avoidance and mitigation measures were expected to avoid adverse effects, and therefore did not require offsets.

Trans Mountain summarized the following potential Project effects on wildlife, including migratory birds, and their habitat:

-

change in habitat from vegetation clearing and sensory disturbance;

-

change in movement from reduced habitat connectivity and creation of barriers or filters to movement; and

-

increased mortality risk resulting from collisions with vehicles or equipment, loss or disruption of habitat features, or sensory disturbance.

Trans Mountain noted that linear disturbances from right of way clearings would result in increased predator efficiency, and improved access for trapping, hunting and poaching of wildlife, leading to potential increases in wildlife mortality.

In order to mitigate these potential effects, Trans Mountain noted that it sited the majority of the Project along existing disturbances to minimize new clearing areas, and avoid areas designated as critical habitat for caribou and grizzly bear populations where feasible.

Trans Mountain further committed to conduct post-construction environmental monitoring for five years to determine the effectiveness of its mitigation and avoidance measures.

The NEB held that destruction of critical habitat for caribou and grizzly bear populations be avoided. Where avoidance is not possible, the NEB directed Trans Mountain to develop and implement a caribou habitat restoration plan to offset any lost habitat from construction and operation of the Project such that there is no net loss of habitat.

The NEB determined that with the above mitigation and offsets, the potential for the Project to adversely impact predator-prey dynamics in the Project area was low.

With respect to marine impacts, Trans Mountain noted that based on information available, the waters surrounding the proposed WMT indicate elevated levels of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, cadmium and mercury, and chronic oil contamination from existing developments. Trans Mountain noted that among the impacts from construction, it would dredge approximately 150,000 cubic meters of intertidal and nearshore subtidal materials. Trans Mountain committed to reducing the total amount of dredging required, and further proposed the following mitigation measures:

-

minimize or completely avoid the dredging footprint required for the WMT;

-

employing clamshell dredging and silt curtains to limit any potential sediment release during dredging;

-

monitor turbidity and suspended solids in the water during construction; and

-

follow erosion and sediment control measures on land to limit sediment release in water.

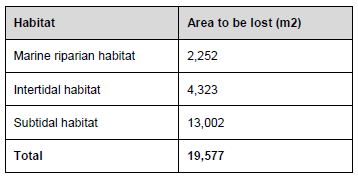

Trans Mountain also estimated the following impacts on marine fish habitat due to the construction of the WMT and tanker berths:

Trans Mountain noted that some marine organisms may be killed during construction due to pile driving, dredging or infilling, although Trans Mountain noted a low abundance of potentially impacted species in the area surrounding the WMT.

The NEB acknowledged the existing water contamination around the WMT, and imposed a condition requiring Trans Mountain to develop and implement a marine sediment management plan, along with monitoring during construction.

The NEB also imposed a follow-up monitoring program on Trans Mountain to assess the effectiveness of Trans Mountain’s proposed mitigation measures, and file these results with the NEB.

The NEB found that Trans Mountain’s ecological risk assessments for the Project were appropriate.

Need for the Project

The NEB noted that it must consider the need for and economic feasibility of the Project under section 52 of the NEB Act, having regard to:

-

The availability of oil, gas or other commodities to the Project;

-

The Existence of markets, actual or potential; and

-

The economic feasibility of the Project.

Accordingly, the NEB noted that it requires applicants to provide the following economic information:

-

Supply – evidence that there is or will be adequate supply to support the use of the pipeline;

-

Transportation – Evidence indicating that the volumes are appropriate for the applied-for facilities, and that they will be utilized at a reasonable level over their economic life;

-

Markets – Evidence indicating that adequate markets exist for the increased volumes available to the marketplace; and

-

Financing – Evidence of the applicant’s ability to finance the facilities, including method of financing, and any changes to the financial risk of the company as well as toll impacts and abandonment cost estimates.

Trans Mountain submitted that the Project was required from a broader public interest perspective, to ensure that the highest value is obtained for produced petroleum resources. Trans Mountain submitted that sufficient pipeline capacity is needed for Western Canadian producers to access the highest value markets, and would support one of the NEB’s stated goals to have Canadians benefit from efficient energy infrastructure.

A consortium of shippers, consisting of Canadian Oil Sands, Devon, Cenovus, Husky Oil, Imperial Oil, Statoil, Suncor, Tesoro and Total (the “TMX Shippers”) submitted that the Project was in the best interest of Canadians to diversity the markets for its oil exports by providing enhanced access to tide water. The Project was similarly supported by the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada.

Trans Mountain submitted that current demand for transportation services on the existing Trans Mountain pipeline exceeds capacity, and results in a need to apportion available capacity. The resulting apportionment of capacity was, in Trans Mountain’s submission, a clear indicator of the value placed by shippers on obtaining access to the west coast and offshore markets.

Trans Mountain submitted that the Project was underpinned by firm commitments of 112,300 cubic meters per day (or 707,500 bpd), representing 80 percent of the nominal capacity on the expanded system. Trans Mountain noted that 13 shippers have signed 15 or 20 year commitments, and demonstrate that the Project can be expected to be utilized at a high rate. Trans Mountain also noted that its shippers are significant players in the petroleum industry and have investment grade or better credit ratings, which would provide assurance for Trans Mountain to meet its long-term financing requirements.

Trans Mountain also submitted that higher prices for Western Canadian Crude would provide total producer benefits of approximately $73.5 billion on an undiscounted basis, and a present value of approximately $38 billion attributable to the market access provided by the Project from 2017-2037. Trans Mountain further estimated the direct federal and provincial benefits to be approximately $23.7 billion over the life of the Project, excluding incremental benefits from refining, processing and downstream activities.

Living Oceans submitted that the contractual capacity does not confirm the need for the Project, given that the contracts were negotiated in 2011 and 2013, and noting that circumstances have changed materially since that time.

Trans Mountain submitted evidence that global benchmark prices for oil are usually identical after accounting for quality and transportation costs, however, this was not the case in recent years for North American markets, with prices lagging considerably. Trans Mountain’s evidence pointed out that the pricing imbalance was primarily due to lack of market diversification for Canadian Crude.

Trans Mountain’s evidence did not address or assume any impacts on the Canadian economy from higher crude oil prices, or any impacts on the refining sector. Trans Mountain also did not factor in Energy East, Keystone XL or Northern Gateway pipelines in its price forecast scenarios, given uncertainty with the tolling and timing information available.

Trans Mountain submitted that Western Canadian crude oil supply is forecast to grow from 635,000 cubic meters per day in 2015 to 1.01 million cubic meters per day in 2038. While Trans Mountain noted that many forecasts differ somewhat in later years, they broadly communicate a significant increase in crude oil supply in the future.

Trans Mountain provided evidence that it did not anticipate the Project acting as a price setting mechanism because it would not transport the marginal or incremental barrel of Western Canadian crude oil.

Trans Mountain submitted that the markets accessed would be in the Burnaby and Puget Sound area, and Northeast Asia, with secondary markets in California and Hawaii. Trans Mountain submitted that refineries in Puget Sound have a combined capacity of 100,410 cubic meters per day, while potential demand from Northeast Asia exceeds 369,700 cubic meters per day. For secondary markets, Trans Mountain submitted that economics of selling to California is made difficult because of high CO2 emissions ratings, as well as the cost of upgrading and refining heavy crude.

With respect to Project financing, Trans Mountain submitted that the total capital cost of the Project would be approximately $5.5 billion, including construction costs of approximately $3.6 billion.

The City of Burnaby submitted that Trans Mountain’s application and evidence provided a distorted and unrealistic picture of the economic impact and economic feasibility of the Project. The City of Burnaby submitted that Trans Mountain misinformed the NEB, obfuscated issues, and withheld pertinent financial and economic information from the record. The City of Burnaby submitted that Kinder Morgan (Trans Mountain’s parent company) was downgraded by three credit ratings agencies in 2014, and was delisted from the New York Stock Exchange, but did not update its application to reflect these developments. Kinder Morgan was recently unsuccessful in gaining an enhanced credit rating above BBB- from Standard and Poor’s, Baa3 from Moody’s and BBB- from Fitch, all of whom identified Kinder Morgan’s vulnerability to a credit downgrade.

Other interveners challenged Trans Mountain’s evidence, stating that Trans Mountain underestimated the amount of capacity that will be in place, and would result in excess capacity. Interveners also submitted that the Project was not needed and that investment was better suited towards building non-polluting energy projects.

The Government of Alberta submitted that improved market access for Canada’s oil and gas industry would substantially increase corporate income taxes, and would further increase employment opportunities across Canada. The Project was supported on similar grounds by the British Columbia Chambers of Commerce and the Edmonton Chambers of Commerce.

The City of Vancouver criticized Trans Mountain’s supply evidence, submitting that the forecasts provided did not account for infrastructure constraints, and effectively assumed construction of other pipelines outside the Project.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers submitted that forecasts show that the rate of supply growth did not change the fact that supply was growing and required increased market access.

British Columbians for Prosperity stated that due to the bottlenecked transportation system for crude oil, and declining demand from the United States, Canada receives a discounted price for its oil. In their submission, the Project would help to rectify the current price discount for Western Canadian crude oil.

The NEB held that increasing pipeline capacity for the purpose of accessing Pacific Basin markets was important to the Canadian economy, which it held was a significant benefit of the Project. The NEB accepted that committed shippers for the Project were seeking growth market alternatives for production, and found that the Project would provide access to these markets.

The NEB held that the forecast supply and market demand growth, combing with robust contractual and financial underpinnings for the Project, demonstrated that the Project would be used and useful over its economic life, and that Trans Mountain would be able to finance the Project.

Financial Matters

The NEB noted that section 52(2)(d) of the NEB Act required the NEB to consider the financial assurances directly related to facilities and activities regulated by the NEB, including financial responsibility and financial structure of Trans Mountain.

Trans Mountain submitted that it was an Alberta unlimited liability corporation, and the general partner of Trans Mountain Pipeline L.P, holding 0.01 percent partnership interest. Trans Mountain submitted that it would hold the CPCN, should it be issued. The Project would be operated by Kinder Morgan Canada Inc.

Trans Mountain submitted that it has unlimited liability for the liabilities and obligations of Trans Mountain L.P. Kinder Morgan Cochin ULC, as the limited partner of Trans Mountain Pipeline L.P, would not be liable to creditors of Trans Mountain L.P. The liability of a limited partner is limited to any amount of its required capital contributions that are unpaid.

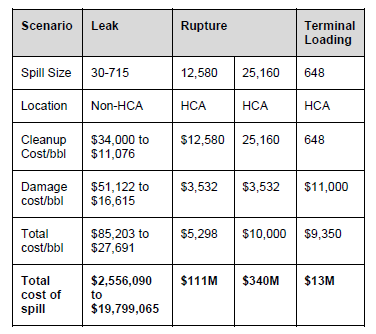

Trans Mountain also filed an expert report to assess the potential costs of oil spills ranging from 4.8 cubic metres, to a 4,000 cubic meter spill on the Project. Trans Mountain examined the costs of spills in high consequence areas (“HCA”), and outside of high consequence areas (“non-HCA”). Trans Mountain submitted the following estimated costs of remediating hypothetical crude oil spills from the Project:

The NEB held that the limited partnership structure of Trans Mountain was acceptable, but that the NEB would impose Condition 121, which requires Trans Mountain to maintain $1.1 billion in financial assurances, since Trans Mountain is responsible for cleaning up the environment and compensating affected parties in the case of an oil spill.

Project-related Increase in Shipping Activities

The NEB found that increased marine shipping to and from the WMT was not part of the Project for the purposes of its inquiry. However, the NEB noted that it would consider the potential effects of shipping activities, and any accidents or malfunctions under the NEB Act. To the extent that there is potential for the effects of the increased marine shipping to interact with the environmental effects of the Project, the NEB noted that it considered such impacts as part of the cumulative effects portion of its environmental assessment.

Order and Conditions

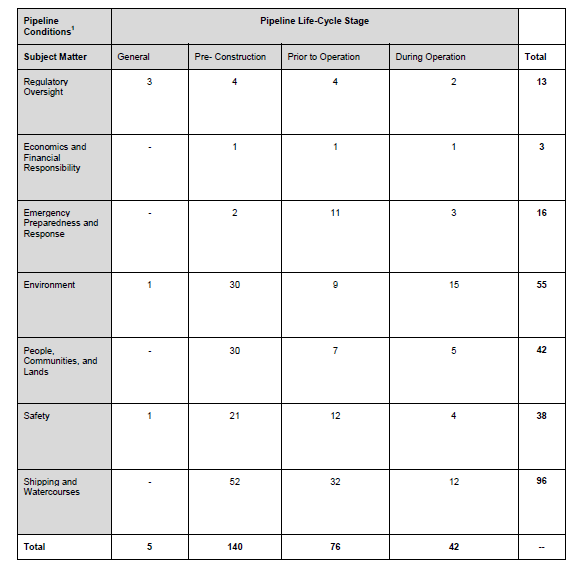

The NEB conditionally approved the Project, imposing 157 conditions on Trans Mountain. The NEB separated the conditions imposed on the Project in two functional categories: subject matter and pipeline life-cycle stage.